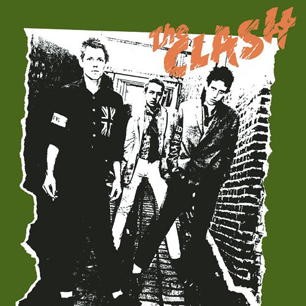

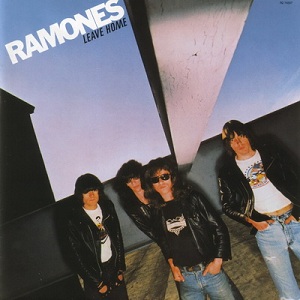

Greetings, readers! So I’m back at the book again here, mining chapter 3, “1977: Clamor, Exposure, and Camaraderie,” for another gem related to the DIY spirit. The clamor, of course, was ringing from speakers on the stage and in bedrooms on both sides of the Atlantic, as 1977 saw the release of the 2nd Ramones’ LP, Talking Heads: 77, Television’s Marquee Moon, The Clash, two LPs each by The Damned and The Stranglers and, almost late in the game, came the debut LP by The Sex Pistols.  The DIY ethos informed the fanzines, too–most notably Mark Perry’s Sniffin’ Glue, which popularized the cut-and-paste ransom-note aesthetic and, for better or worse, fomented the yer-either-with-us-or-against-us ethos that led to a narrow definition of punk.

The DIY ethos informed the fanzines, too–most notably Mark Perry’s Sniffin’ Glue, which popularized the cut-and-paste ransom-note aesthetic and, for better or worse, fomented the yer-either-with-us-or-against-us ethos that led to a narrow definition of punk.

Perry’s search in ’76 for written coverage of his new favorite bands turned up almost nothing. “One time I was at [the record shop] Rock On, trying to find out if there were any magazines I could read about these bands in,” Perry recalled. “There weren’t, so the people behind the counter suggested flippantly that I should go and start my own. So I did” (Stealing, p. 42). And did so quickly, and with a sensibility that’s been confirmed nearly four decades hence, as the cover of issue #6 from January ’77 rightly confirms. Perry, too, knew that before too long, his subjects were also his readers. “John Lydon had it, Strummer had it, Rat Scabies had it,” Perry reported. “I thought, ‘If I say this in the Glue, it’s going to happen.’ I knew that, and that’s what fueled me, knowing that it was being taken seriously” (Ibid.).

Perry, alas, took himself too seriously, and did so for years. You might think after a couple decades he might back away from punk-inspired claims such as, “Punk died the day The Clash signed to CBS,” but no. For John Robb’s Punk Rock, Perry stuck to his ideological guns:

“These guys weren’t about to smash their Gibson & Fender guitars all over the stage, were they? … they manipulated punk into ‘OK, we won’t have a riot, we will sing about it instead.’ Which is cool, at least someone’s singing about it — but don’t try to make out that are some hard revolutionary. You’re just in a pop band — which the Clash ended up being. They were a great pop band, but nothing to do with punk. The real punk bands came a couple of years later, the bands we all hated like the Exploited and all those nasty working-class people [laughs] that have convictions and have been in trouble with the police …” (p. 340).

So, the requisite credentials include: smashing expensive gear, trouble with the law, and you need to be as tedious as The Exploited? As a period piece, The Exploited were perfect, but how many times can you listen to songs that repeat the same phrase in a chorus and construct musical bridges from watered down heavy metal riffs?

Punk is a many-a-splendored thing and, as guitarist Marco Pirroni rightly noted, “This whole Mark P thing that [the Pistols] should sign to Bumhole Records for no money was stupid — that would never work.” The Clash’s refusal to become a self-parody by making the same album over and over again is a testament to their greatness, not a failure. And please: if we’re talking about class credentials, lay off Mick Jones. “Rock’n’roll Mick” did what any poor boy with enough pounds for a guitar and an unassailable work ethic would do: he dedicated his life to rock’n’roll, and made the world a better place.

I will give Mark P. due credit, though, for rocking Alternative TV well into the 21st century–and tonight, 8 March, in Brighton. Cheers!